To grapple with our own complicity with violence

FOR SLOVENIAN VERSION OF THE INTERVIEW CLICK HERE

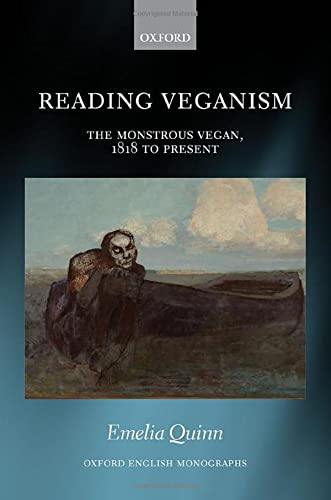

I interviewed Dr. Emelia Quinn, who is an Assistant Professor of World Literatures & Environmental Humanities at the University of Amsterdam. Her work informs the field of vegan theory and its intersections with animal studies, queer theory, and postcolonial studies. She is the author of a book titled Reading Veganism: The Monstrous Vegan, 1818 to Present (Oxford University Press, 2021) and the co-editor of Thinking Veganism in Literature and Culture: Towards a Vegan Theory (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). We talked about vegan studies, »the monstrous vegan« in literature, veganism and camp as a political means, as well as about the possibilities of vegan humour in animal rights activism.

Anja Radaljac: How did you first start to get involved in the animal liberation movement and how did your experiences with political movements before that influence your approach to animal rights?

Emelia Quinn: I was born and raised as a vegetarian so was first engaged with the ethical imperatives against meat-eating through my upbringing. My mother was not actively involved in the animal liberation movement but had a deep personal commitment to vegetarianism and was ardent in her commitment to raise both my sister and I as vegetarians.

I remained vegetarian throughout my life and went vegan at the age of 20 after stumbling upon a post on Facebook about the grinding of live baby chicks as a routine part of the egg industry. On doing further research I discovered that the practices that went on in the egg and dairy industry did not align with my ethical vegetarian commitments. I was embarrassed that it had taken me so long to become aware of these realities and worried that my vegetarian commitments had blinded me to further exploring and researching the realities of industrial farming. This realization saw me become much more active in my approach to animal liberation and led to me thinking about how my personal veganism might impact upon my academic work and what we might gain from thinking about veganism in the academy.

These formative experiences rather than any other political movements were how I got involved in animal liberation. That said, I feel reluctant about claiming I am involved in any direct way the animal liberation movement given my limited work in activist circles. My commitment to animal liberation is channeled instead through my academic work, in the hope that theory constitutes a form of activism.

AR: At the event Veganism and multi-species justice organized by Global Conversations Towards Queer Social Justice you talked about camp aesthetics as a political stance and a form of rebellion in the queer community. Can you tell our readers a bit more about what is camp aesthetics, how is it linked to the queer community and movement, and how it can be seen as a political tool?

EQ: The most famous attempt to define camp was made in Susan Sontag’s 1964 article “Notes on Camp.” Sontag describes camp as a “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration” (275). For Sontag, camp is a refusal to see content beyond surface and works to convert the serious into frivolous. In its refusal to take things seriously, camp is an aesthetic lens that revels in stylization and extravagance and expresses a love “of things-being-what-they-are-not” (279). While an important foundational work of camp definition, Sontag’s work has been criticized in several different ways. One of the most prominent critiques focuses on her depoliticization of camp, arguing that “It goes without saying that Camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticized—or at least apolitical” (277).

Camp is rooted in queer communities and has functioned historically as a means of queer community building. Contemporary scholars tend to reinvest in the political possibilities of camp, with the building of queer community enacted through camp seen as a strategy of resistance. For Ann Pellegrini, camp is not apolitical hedonism but a re-imagining of the world that demonstrates queer social agency. Camp can reappropriate damaging queer stereotypes in order to offer critiques of oppressive social realities. Drag performances are a useful exemplification of what camp does. Drag embraces the excessive and heavily stylized and revels in artifice but it offers also a critique and explosion of heteronormative gender norms, drawing attention to the performative dimensions of gender.

AR: In your article Notes on Vegan Camp you’re researching camp aesthetics in the vegan movement. How did you come upon this topic and why you took interest in it?

EQ: My article “Notes on Vegan Camp” was the result of an invitation to speak at a symposium about the “Turner and the Whale” exhibition on display at the Hull Maritime Museum in the UK (2017-2018). I was invited by a previous professor of mine who wanted me to bring a vegan theoretical perspective to the event. I was asked to choose a singular object from the collection, comprised of paintings and artefacts associated with nineteenth-century whaling culture, and to prepare a position paper based on it. I initially had great difficulty with this. One, because I felt insecure about my ability to do an art historical reading. And two, because I feared that I would have little to say from a vegan perspective about such artefacts. What was there to say beyond drawing attention to the horror of whaling and condemning my chosen object as a relic of atrocity? I felt there was little originality to such a response: I would be saying only what would be expected of any vegan commentator. However, this changed when I came across a piece of scrimshaw in the collection titled “The Jolly Sailor.”

Scrimshaw refers to engravings on whale bone or teeth and was a popular pastime upon whaling ships in the nineteenth century. There was a wealth of scrimshaw on display at the Hull Maritime museum, ranging from patriotic portraits to whaling scenes. However, the Jolly Sailor stood out for its irresistibly kitschy aesthetic. As I describe the piece in my article “Notes on Vegan Camp,” “[The jolly sailor] stands legs akimbo in a pose of triumph, waving his straw hat in the air on board the fifthrate warship the Cornelia, the name of which is proudly emblazoned on his shirt. With his posture both invoking and flaunting his resistance to a self-sacrificial crucifixion pose, he is surrounded by an excessive display of imperial ambition: the Royal Navy’s White Ensign, which he is planting on the deck of the ship, and a cannon prominently visible between his legs, a display of military strength as much as one of male virility” (920).

What was therefore most notable about this piece was that I found that I couldn’t immediately condemn it or mourn the slaughtered whale who had provided the tooth. Instead I found that the piece evoked aesthetic delight. So, this encounter led me to think more carefully about what exactly was entailed in a vegan aesthetic response. The dominant narrative for vegan aesthetics is typified by the quote often touted by PETA that “If slaughterhouses had glass walls, everybody would be a vegetarian.” This is a narrative based on the importance of exposure to, and witnessing of, violence towards animals. However, I wanted to question what we were to do when our aesthetic responses didn’t neatly match up with our vegan ethics. How could we think critically about vegan pleasures?

Vegan camp was my attempt to theorise the pleasure gained through the Jolly Sailor scrimshaw. I suggested that the scrimshaw offered a satirical commentary on male imperial ambition. Indeed, that the slaughtered sperm whale was not itself enough of a display of human triumph seemed to say a lot about the insecurities of nineteenth century masculinity. The camp quality to the piece also saw me reflect back on the homoeroticism of the whaling ship in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and think about the possible interconnections between queer and vegan camp. Ultimately a vegan camp lens offered me a means of rehabilitating my vegan pleasure in the service of satirical critiques of human exceptionalism, submitting the desperation of the human to assert dominance over the nonhuman animal to farce.

AR: Could you compare the function of camp in queer and the vegan movement? What could be some turnaround points that the camp can offer veganism?

EQ: In queer movements camp is often a survival strategy for gay men. It represents a reparative mode of looking that, as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick argues, is demonstrative of “the many ways selves and communities succeed in extracting sustenance from the objects of a culture—even of a culture whose avowed desired has often been to sustain them” (150-151). In a similar fashion, vegan camp seeks to draw pleasure from objects that might otherwise wound vegans; objects representative of the traumatic encounter of the reality of a mass violence against nonhuman animals to which we, as individual vegans, are powerless to stop. I therefore see vegan camp as a survival strategy for individual vegans, offering a means of relief and community identity in the face of relentless horror.

However, the key difference here, as you note in your next question, is that queer camp is an aesthetic claimed by the queer community, for the queer community. In contrast, vegan camp is an aesthetic claimed by individual vegans and seems more invested in human identity politics – and the category of vegan experience – than it does about the nonhuman animals whose suffering is at the heart of a vegan camp response. There is a huge risk here of devaluing the animal lives displayed for vegan camp enjoyment. I’ll address this risk below.

AR: Could there be any ethical problems that would arise in the vegan camp such as the proposed meat dress that Lady Gaga wore? What about the fact that when camp is turning the pain into pleasure – or reappropriating pain – in the queer movement this is the pain of queer people themselves, but in the case of the vegan movement there is the suffering of non-human animals being turned into pleasure …?

EQ: One of the most important things I note in my article about vegan camp is its inextricable relationship to complicity. In laughing at or gaining pleasure from objects such as Lady Gaga’s meat dress we are performing a certain mode of complicity. In Carol J. Adams’s work it would be important to re-member the dead cow(s) slaughtered to make Gaga’s dress. In refusing to do this and focusing only on the surface of the dress in a vegan camp reading, we become complicit in the objectification of the nonhuman animal body. What vegan camp recognises is that re-membering the dead animal is not the only means of vegan response. A vegan camp embrace of the dress as a satire of human exceptionalism, and, in particular, a satire of heteronormative ideas of meat and female sexuality, offers a way of reclaiming such an object for vegan ends. As I note in my article, “The focus on surfaces refuses the symbolic values that assign personhood as a humanist Cartesian subjectivity. The surface of flesh does not return to a prediscursive site, in the recognition and return of the absent referent animal, but becomes visible as a surface-level depiction of the discursively constructed nature of our desires and identities. Acknowledging the fun and whimsy of this revelation is one of several possible vegan strategies for confronting the world” (“Vegan Camp” 923).

The performance of complicity in violence offers a sense of veganism as an identity that must continually grapples with its own failures and insufficiencies, disruptive of mainstream stereotypes of vegans as self-righteous virtue-signallers. As I note in an article reading the wood carvings of Grinling Gibbons through a vegan camp lens, “While vegan camp might seem to offer a form of consolation in the retrieval of joy and pleasure for the vegan subject otherwise haunted by paralysing images of violence, it refuses a consolatory redemption. This is achieved by actively performing and therefore acknowledging a complicity in violence, as well as through the queer abjection haunting the camp as a category of experience” (“Attendance” 392).

AR: Vegan movement is a very serious one … there is just so much pain and suffering that seems endless. Are, other than camp, there any other ways of making room for humor in the vegan movement? Maybe something like Vegan Sidekick comics?

I think the use of humour in the vegan movement is becoming more and more popular. Simon Amstell’s 2017 mockumentary Carnage is, I think, a particularly effective example of the power of humour in the vegan movement. The satirical portrayal of vegans in the 2017 Palme d’Or nominated Okja, in a film otherwise explicit in its vegan messaging, also demonstrates an increasing willingness for vegans to laugh at themselves and to perform the impossibilities and contradictions of a vegan position.

Nicole Seymour also has a great chapter on veganism and satire in the forthcoming Edinburgh Companion to Vegan Literary Studies that I have been co-editing alongside Laura Wright. Seymour offers in her piece an excellent analysis of the Vegan Sidekick comics and their affects, offering a survey of the various ways in which satire has been used across both vegan and anti-vegan media.

More broadly I see the growth in the mock meat market as another potential form of pleasure and humour in the vegan movement. Increasingly absurd true-to-life mock meat products seems to offer, as I argue in my vegan camp piece, a dismantling of carnivorous investments in meat and provide vegans with a carnivalesque site of subversion of meat-eating cultures.

AR: Other than the vegan camp, you’ve been researching veganism in Anglophonic literature from 1818 to the present; you’ve published a book Reading Veganism: The Monstrous Vegan, 1818 to Present. Who is the “monstrous vegan” in the title? How did this figure evolve through literature?

EQ: The “monstrous vegan” of the title of the book represents a literary trope that I have identified as re-appearing in multiple guises across the past 200 years of Anglophone literature. I posit the origins of the monstrous vegan trope with the vegetarian monster of Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein and then demonstrate how this figure has been rewritten and revised throughout literary history. Monstrous vegan literary figures draw attention to the anxieties and tensions generated by attempts to inscribe a pre-existing discursive vegan code onto the corporeal body, and therefore to questions of what it means to read and write veganism.

I argue that we can recognize the monstrous vegan in relation to four key tropes:

First, monstrous vegans do not eat animals, an abstinence that generates a seemingly inexplicable anxiety in those who encounter them. Second, they are hybrid assemblages of human and nonhuman animal parts, destabilizing species boundaries. Third, monstrous vegans are sired outside of heterosexual reproduction, the product of male acts of creation. And, finally, monstrous vegans are intimately connected to acts of writing and literary creation. These traits provide a blueprint for recognising iterations of the monstrous vegan in the literary canon.

The book is divided into two parts. Part 1 charts a literary history of monstrous vegan, suggesting a trajectory whereby the monstrous vegan is transformed from a figure through which Shelley invests in Romantic ideals of a prelapsarian vegetarian Eden at the origins of man through to a figure that appears in Margaret Atwood’s contemporary fiction as a manifestation of the monstrous results of veganism: a patriarchal discourse inscribed onto bodies that attempts to negate individual agency. Here the monstrous vegan remains a consistent source of anxiety but transforms into a figure representative of false projections of innocence. This trajectory seems to leave us with a sense of futility.

However, in Part II of the book I explore two contemporary iterations of the monstrous vegan in works by J. M. Coetzee and Alan Hollinghurst. I argue in these chapters that these contemporary novelists are engaging with the monstrous vegan in order to explore the productive possibilities to be found through performing monstrous veganism, as a temporary means of escape from haunting knowledge (in Coetzee) and as a means of vegan camp play (in Hollinghurst).

AR: The novel Frankenstein is one of the works of literary fiction that are most important for animal studies – why is that? What is the “vegan monster” like in Frankenstein? What are some of the dichotomies – in the relation to being human and human relation to other animals – that Frankenstein encapsulate?

EQ: The importance of Frankenstein for literary animal studies really begins with Adams’s foundational analysis of novel in her 1990 text The Sexual Politics of Meat. Here Adams establishes the vegetarianism to be found at the heart of Shelley’s narrative and contextualises Shelley in relation to the contemporaneous vegetarian radical circles she was a part of. Adams’s analysis not only evidences the importance of vegetarianism in Frankenstein but demonstrates through her analysis the ways in which contexts of vegetarianism, particularly as they are related to feminist commitments, have gone unacknowledged in previous literary scholarship. For Adams, acknowledging the vegetarian contexts influencing Shelley during the conception of Frankenstein is a vital means of understanding Shelley’s feminist politics.

The “vegan monster” in Frankenstein is a creature assembled from parts pilfered from both the charnel house and the slaughterhouse by the novel’s protagonist, Victor Frankenstein. While the creature is often portrayed in mainstream culture as a solely monstrous figure, this doesn’t do justice to the sympathetic first-person account of his life found at the heart of the novel. Part of his sympathetic self-presentation is expressed through his vegetarianism. After fleeing from Victor Frankenstein’s laboratory, the creature sustains himself on nuts, acorns, roots, cheese, and bread and argues of his essentially peaceful and benevolent nature in the following terms: “My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid, to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment” (120). This diet of acorns and berries associates the monster with a prelapsarian Eden and alludes to ideas that were popular at the time of a vegetarian Golden Age that came before the fall of man. He begs of Victor to make him a female mate and dreams of an exile in South America together where “the sun will shine on us as on man and will ripen our food” (120).

This evocation of a world before the advent of fire ties into the Promethean metaphors found throughout the novel (it is worth noting too that the subtitle given to the novel by Shelley was “Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus”). The myth of Prometheus is the Greek myth whereby Prometheus stole fire from the Gods and gave it to humanity. For Percy Shelley, Mary’s husband and famous poet, the gift of fire to humanity was the origin of our fall from Grace. In his extensive notes to his early radical poem “Queen Mab,” Percy posited fire as the advent of meat-eating by enabling meat to be palatable to humans. To quote Percy, “Prometheus (who represents the human race) effected some great change in the condition of his nature, and applied fire to culinary purposes; thus inventing an expedient for screening from his disgust the horrors of the shambles” (108). Percy then suggests that this use of fire was the root cause of evil in the world and posits the rejection of both meat and alcohol as a solution to, variously: disease, crime, mental and bodily derangement, the vice of commerce and avarice of commercial monopoly, the desire of tyranny, class inequality, unsustainable land use, food waste, and national security, amongst numerous other social ills. So with this context in mind, the creature’s fireless vision of the future, of berries ripened by the sun, comes to signal a cyclical return to a pre-Promethean vegetarian Eden and inscribes vegetarianism onto the body: as the original corporeal state of mankind.

AR: What can literature tell us about a vegan identity and societal view on this identity? How do you understand veganism as identity and what are some of the ways that should be expanded and understood beyond what is seen in mainstream culture? What are some of its inconsistencies and complications?

EQ: While veganism is often adopted for many different reasons, upon ethical, environmental, health, and economic grounds, amongst others, my definition of veganism is grounded in the combination of belief and action that seeks the end of the exploitative use of nonhuman animals for human benefit. Recognition of the suffering of nonhuman animals is, for me, central to the definition of vegan practice and its end is constitutive of the kernel of utopian desire undergirding it. In this understanding of veganism, it is about much more than simply what we put in our mouths but a deeply felt ethical position and approach to the world.

The UK Vegan Society offers the following definition of veganism, formulated when it became a registered charity in 1979, that is also helpful in understanding this negotiation of failure and utopianism: “a philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude—as far as is possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose; and by extension, promotes the development and use of animal-free alternatives for the benefit of humans, animals and the environment. In dietary terms it denotes the practice of dispensing with all products derived wholly or partly from animals.” While the “dietary terms” of veganism appear with certainty, “dispensing with all products derived wholly or partly from animals,” this definition frames veganism as “a philosophy and way of living” within the hyphenated clause “as far as is possible and practicable.” Thus, while striving towards the end of exploitation, this definition of veganism is tethered to the burdens of its impossibly inclusive aspirations, reliant on a recognition of that which is neither possible nor practicable.

I see veganism as a helpful label, politically and socially. However, I don’t necessarily believe that we should see it as a fixed or static concept that can be concretely defined. The active acknowledgement of the contradictions and inconsistencies embedded within vegan practice, because of the impossibility of being truly vegan in all aspects of our lives, invites a recognition of veganism’s complicity and collusion with dominant systems of oppression. This runs counter to many mainstream preconceptions of veganism, associated with moral righteousness or a fascistic quest for purity. Such a recognition also stands in contrast to veganism’s frequent association with a naive and sentimental love of nonhuman animals, as well as with a white, middle-class subjectivity. The latter association positions veganism in relation to white privilege, where concern for the nonhuman comes at the expense of concern for the structural oppressions facing disenfranchized humans. I am interested, by contrast, with the ways in which veganism functions as a utopian aspiration that must learn to grapple with an often inescapable complicity in abhorrent systems.

For me, vegan literary studies provides a mode of reading that grapples with the multiple contradictions and failures embedded in the enactment of a vegan life and as embodied by vegan readers and scholars, as well as with the utopian impulses and aspirations that sustain it. In my theorization of vegan reading practices, books don’t therefore have to contain vegan characters for us to read them in a vegan way. Vegan literary studies need not be only about vegan polemics or pro-vegan texts. In my own work I apply a vegan theoretical lens to texts that are, at least on the surface, actively hostile to veganism as an identity and way of life.

AR: What is the vegan theory, how does it understand the world and sociopolitical relations, and how it can help the vegan movement reach its goals?

EQ: Vegan theory represents a broad and interdisciplinary attempt to think seriously about veganism as an approach to the world. In my conception of vegan theory, as described above, veganism is a locus point for thinking about the occupation of the dual poles of insufficiency and utopianism. It is a way of grappling with complexity and difficulty while remaining committed to the ethical treatment of nonhuman animals.

I believe such a theoretical treatment of veganism is necessary in order to disrupt mainstream misconceptions of veganism as a movement about purity and perfection. Such misconceptions tend to associate veganism with moral righteousness. This can be off-putting to potential vegan converts but it also does a disservice to veganism itself. Veganism is not to be mistaken for a consumerist trend, or a series of rigid proscriptions, but represents an active engagement with the ongoing difficulties of living an ethical life. I also think such a re-conception of veganism allows us to occupy a more monstrous vegan identity, something that allows us to acknowledge and grapple with our own complicity with violence.

Works Cited

- Adams, Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist Vegetarian Critical Theory. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

- Pellegrini, Ann. “After Sontag: Future Notes on Camp.” A Companion to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Studies, edited by George E. Haggerty and Molly McGarry. Wiley Blackwell, 2007, pp. 168-193.

- Quinn, Emelia. Reading Veganism: The Monstrous Vegan, 1818 to Present. Oxford UP, 2021

- —. “Notes on Vegan Camp.” PMLA, vol. 135, no. 5, pp. 914-30.

- —. “Vegan Attendance: Reading Gibbons’s Animals.” The Sculpture Journal, vol. 29, no. 3, 2020, pp. 378-393.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You.” Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, edited by Adam Frank. Duke UP, 2003, pp. 123-152.

- Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. The 1818 Text. Oxford UP, 2008.

- Sontag, Susan. “Notes on Camp.” ‘Against Interpretation’ and Other Essays. Penguin Classics, 2009, pp. 275-292.

Anja Radaljac

Sem literarna in gledališka kritičarka ter prozaistka. Od leta 2016 se aktivno ukvarjam z naslavljanjem vprašanja ne-človeških zavestnih, čutečih bitij skozi izobraževalne vsebine. Leta 2016 sem izdala esejistični roman Puščava, klet, katakombe, ki skozi intersekcijsko obravnavo umešča vprašanje živali v širše družbeno polje. V okviru veganskega aktivizma sem izvajala predavanja po srednjih šolah v Sloveniji, priredila več predavanj in delavnic za nevegansko populacijo, izvajala pa sem tudi delavnice za veganske aktivistke_e. Od leta 2016 do začetka 2019 sem vodila izobraževalni video-blog ter Facebook stran Travožer.